The Old World Meets The New World

While daily life was certainly different for the Colonial settlers than it is today, the basics of the early American diet will be familiar to most of us. Meats such as pork, beef, chicken, fish and lamb were common, as well as most of the fruits and vegetables we eat today (Kalman & Brown, 2002, pp. 14-15). Bread and other baked goods were served at nearly every meal, and coffee and tea were as popular then as they are now (Ichord, 1998, p. 46).

Dinner was the big meal of the day, usually served in the middle of the afternoon. Meat was usually the center of the meal, and the more affluent the family, the bigger the spread. Following the customs of the English motherland, "the table itself might be almost covered with large roast of meat on platters, whole fowls, boiled or baked fish, as well as supplementary meat dishes, game birds, sometimes seafood casseroles, and the home-grown and distinctly Anglo-Saxon puddings, pastries, jellies, and the inescapable sweetmeats of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries" (Jones, 1981, p. 7). Dinner leftovers were often eaten at supper or at breakfast the next day (Troupe, 2012, p. 10).

Dinner was the big meal of the day, usually served in the middle of the afternoon. Meat was usually the center of the meal, and the more affluent the family, the bigger the spread. Following the customs of the English motherland, "the table itself might be almost covered with large roast of meat on platters, whole fowls, boiled or baked fish, as well as supplementary meat dishes, game birds, sometimes seafood casseroles, and the home-grown and distinctly Anglo-Saxon puddings, pastries, jellies, and the inescapable sweetmeats of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries" (Jones, 1981, p. 7). Dinner leftovers were often eaten at supper or at breakfast the next day (Troupe, 2012, p. 10).

Meats

Colonial settlers enjoyed many of the everyday meats we enjoy now. Indeed, in Hannah Glasse's popular 1747 collection titled The Art of Cookery Made Plain & Easy, there are directions included for preparing beef, mutton and lamb, veal, pork, and turkey. In addition to these better-known meats, colonists often made use of whatever animal they could find. In the Glasse book there are sections detailing how to prepare hare, rabbit, teal, pigeons, larks, partridges, plovers, crawfish and others. To add to these traditional English animals, colonists found and ate beasts more common to North America as well: "Venison, pork, fish, eel, turtle, squirrel, and even nuts were often added to the soup pot" (Ichord, 1998, p. 26).

The settlers didn't waste much either—animal parts and sections that modern Americans aren't used to eating were often consumed at the Colonial table, including cocks combs, pigs feet and ears, calf's and sheep's head, chitterlings, beef tongue and udders. The colonists "considered animal organs, like hearts and brains, tasty delicacies" (Crews, 2004, para. 10).

The settlers didn't waste much either—animal parts and sections that modern Americans aren't used to eating were often consumed at the Colonial table, including cocks combs, pigs feet and ears, calf's and sheep's head, chitterlings, beef tongue and udders. The colonists "considered animal organs, like hearts and brains, tasty delicacies" (Crews, 2004, para. 10).

Vegetables

By the mid-1700s, settlers in the colonies had learned how to grow healthy gardens full of a wide variety of vegetables, including cucumbers, beans, carrots, asparagus, spinach, peas, onions, turnips, radishes, artichokes, cauliflower, broccoli, lettuce and potatoes (Jones, 1981, pp. 7-8). The initial disdain for Indian corn long gone, this culinary staple of the Native Americans would be featured in the first cookbook written by an American: Amelia Simmons in her 1796 American Cookery, in the form of "Indian Pudding," "Johny Cake, or Hoe Cake," and "Indian Slapjack."

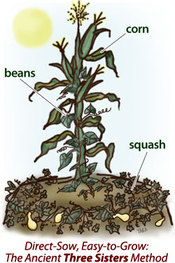

The Native Americans also showed settlers how to plant corn, beans and squash together, and called these crops the 'Three Sisters' (Fisher, 2010, p. 23). The beans and squash plants were situated "between rows of cornstalks. The stalks acted as posts for the bean vines to climb. The squash plants kept the ground shaded and moist so the corn and beans could grow" (Kalman & Brown, 2002, p. 28).

One vegetable commonly enjoyed today that the settlers wouldn't touch was the tomato. The plant's resemblance to deadly nightshade had colonists convinced it was deadly too. "During Colonial times, we wouldn't put a tomato near our mouths, let alone try to eat one. Folklore had it that if you ate a tomato, its poison would turn your blood into acid. Instead, the colonists grew tomatoes purely for decoration" (Sparky Boy Enterprises, 2006, para. 1).

The Native Americans also showed settlers how to plant corn, beans and squash together, and called these crops the 'Three Sisters' (Fisher, 2010, p. 23). The beans and squash plants were situated "between rows of cornstalks. The stalks acted as posts for the bean vines to climb. The squash plants kept the ground shaded and moist so the corn and beans could grow" (Kalman & Brown, 2002, p. 28).

One vegetable commonly enjoyed today that the settlers wouldn't touch was the tomato. The plant's resemblance to deadly nightshade had colonists convinced it was deadly too. "During Colonial times, we wouldn't put a tomato near our mouths, let alone try to eat one. Folklore had it that if you ate a tomato, its poison would turn your blood into acid. Instead, the colonists grew tomatoes purely for decoration" (Sparky Boy Enterprises, 2006, para. 1).

Fruits

Colonists originally planted fruit trees using seeds they brought from Europe, including "apple, pear, cherry, and plum trees" (Kalman & Brown, 2002, p. 14). In contrast to our habits of today, "raw fruits and vegetables were considered unappetizing. So the kitchen help usually cooked them" (Crews, 2004, para. 10). Apples were especially popular, and were used to make apple butter, dumplings, cider, and pies. By the late 1700s, colonists were using a wide variety of fruits in addition to these, according to American Cookery. Instructions are included for making "cramberry," "appricot" and gooseberry tarts, as well as apple and "pompkin" puddings.

Breads and Cakes

By the mid-1700s, the settlers had successfully established healthy crops of traditional English grains. "Rye, oats, and wheat increased throughout the eighteenth century, even as Indian corn continued to dominate. Rye and oats grew more prolifically than wheat, which—for all its centrality to the English diet—remained a novelty, even for the wealthier classes" (McWilliams, 2005, p. 83).

Judging by the number of bread, cake, and biscuit recipes included in American Cookery, colonists definitely seemed fond of these. Many of them will be recognizable by the modern cook, including honey cake, tea cakes and biscuits, pound cake, gingerbread and butter biscuits. One breakfast dish that's not so common today are Johnny Cakes, also called Indian or Journey Cakes. A sort of pancake made with cornmeal, these were a special favorite of George Washington, who liked his "swimming in butter and honey" (Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, 2011, para. 7).

Judging by the number of bread, cake, and biscuit recipes included in American Cookery, colonists definitely seemed fond of these. Many of them will be recognizable by the modern cook, including honey cake, tea cakes and biscuits, pound cake, gingerbread and butter biscuits. One breakfast dish that's not so common today are Johnny Cakes, also called Indian or Journey Cakes. A sort of pancake made with cornmeal, these were a special favorite of George Washington, who liked his "swimming in butter and honey" (Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, 2011, para. 7).

Herbs, Condiments and Sweeteners

Many herbs were cultivated by the early settlers in order to enhance and augment flavors in their cooking. Several varieties were grown for use in medicines as well. Kowalchik and Hylton (1987) state that in the Colonial garden, "herbs were at least as important as the vegetables, and they grew an impressive variety. Lavender, rosemary, thyme, savory, sage, germander, hyssop, southernwood, lavender cotton, dill, chamomile, caraway, fennel, lemon balm, mint, basil, parsley, borage, chervil, tarragon, rue, comfrey, and licorice were all in colonial gardens" (p. 328).

Our Colonial ancestors used ketchup, although it wasn't the thick tomato-based type so popular today. Their ketchups had more in common with our worcestershire sauces, and "originally meant brine of pickled shellfish" (Moss and Hoffman, 2001, p. 25). Other common table sauces and condiments included salt, pepper, mustard, gravy, and traveling sauce. The latter was perfect for those times when a journeying Colonist might find himself in a rural area without a cook up to his high standard—he could use the sauce to add interest to an otherwise bland dish!

Our Colonial ancestors used ketchup, although it wasn't the thick tomato-based type so popular today. Their ketchups had more in common with our worcestershire sauces, and "originally meant brine of pickled shellfish" (Moss and Hoffman, 2001, p. 25). Other common table sauces and condiments included salt, pepper, mustard, gravy, and traveling sauce. The latter was perfect for those times when a journeying Colonist might find himself in a rural area without a cook up to his high standard—he could use the sauce to add interest to an otherwise bland dish!

The folks at Jas. Townsend & Son use authentic 18th century techniques to make mushroom ketchup in this video.

Sugar had to be imported from the West Indies at relatively high cost (Fisher, 2010, p. 13). Loaf sugar (or cone sugar, see photo at top of this page) was "four times as expensive as brown sugar...One cone of loaf sugar usually weighed 8 to 10 pounds. A rural family might have only one cone of sugar for the entire year" (Moss and Hoffman, 2001, p. 63). Other sweeteners the settlers used include honey and maple sugar and syrup.

Title photo: Sugar (in the conical blue wrapper at right), a mortar and pestle and other tools and ingredients on display at Old Salem in Winston-Salem, NC. Taken in March 2012 by Brooks Jones.